First, it's probably not dead.

It could be, but it's not the first thing to guess. Transformers are in general quite durable. They fail two ways: being overheated and being punctured by too-high voltage.

When they fail, there are three kinds of failures possible. These are:

1. A winding burns open and will not conduct at all.

2. A winding shorts, possibly (a) to an adjacent turn, (b) to another winding or ( c) to the core.

3. A winding has an intermittent short or open, possibly intermittent with vibration or temperature.

You can test for items 1 and 2. Since failures of transformers in general are unusual, the intermittent failures of item 3 are downright rare. Not impossible, but rare.

To test a transformer, you need

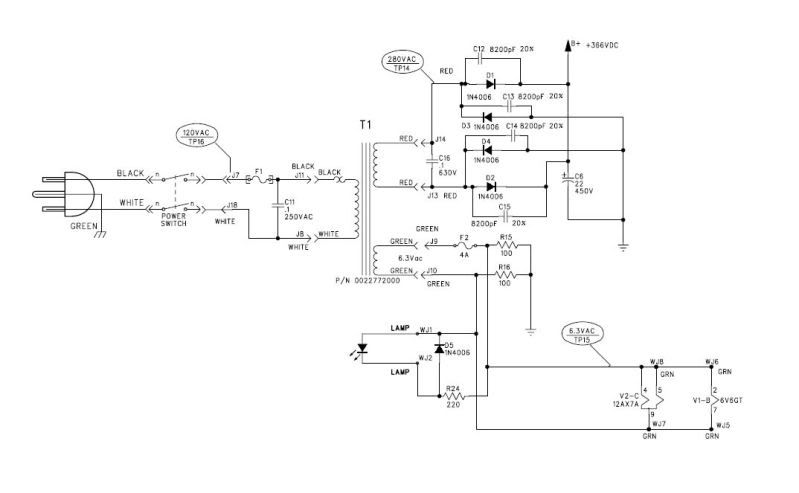

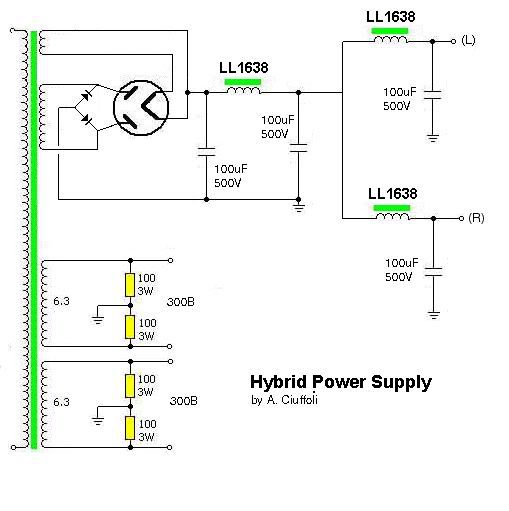

- an application schematic, showing how it's connected, particularly what transformer leads are connected to internal windings

- a multimeter that will measure AC volts and ohms

- a source of low voltage AC, like a filament transformer output

- a neon bulb, like an NE-2

- a battery; the 6V lantern/flashlight battery is ideal.

Test 1: Winding shorts and opens

- Disconnect the transformer from the circuit so the circuit does not give you false readings.

- Set your multimeter to ohms and measure the resistance of each winding. You're looking not for a specific value of ohms, but for the difference between a possibly long length of copper wire and an open circuit. Windings may be a fraction of an ohm, or may be a few hundred ohms. But they are NOT 1M or over. So it's easy to tell.

Each lead shown on the schematic as being connected to a continuous winding must show *not* open circuit to all other leads on that winding. If one or more leads on a winding are open to the others, the transformer has failed. Then measure resistance between windings; it doesn't matter which of the leads on the windings you pick, as the resistance between any two leads on different windings *MUST* be an open circuit.

If there is a resistance, or worse yet a very low ohms value, and the schematic does not show that they are connected, there is an internal short. Notice that you MUST open up any external connections that may cause an external connection of the two. Two unused leads accidentally touching each other or the chassis can cause a false positive.

- Make sure *all* windings are open. Connect the neon bulb across any winding. Doesn't matter which one. Pick a winding, doesn't matter which one, and temporarily connect it across the lantern battery. If the neon bulb flashes when you remove the connection to the battery, there is no internal short inside a winding. Notice that any external loading or connections can show a false failure on this one.

- If it passes all that, it's almost certainly good. To be extra sure, again make sure that all leads are open, and then connect the low voltage AC source to one winding. Low voltage windings are preferable but not critical. Measure the AC voltage on each winding section. There should be an AC voltage proportional to the winding's ratio to the winding being driven.

That's it. If it passes all of those, the only possible flaws left inside are latent ones, things that only short or open under high voltage stress or high temperatures. As noted, these do occur, but are quite rare.

Questions?

It could be, but it's not the first thing to guess. Transformers are in general quite durable. They fail two ways: being overheated and being punctured by too-high voltage.

When they fail, there are three kinds of failures possible. These are:

1. A winding burns open and will not conduct at all.

2. A winding shorts, possibly (a) to an adjacent turn, (b) to another winding or ( c) to the core.

3. A winding has an intermittent short or open, possibly intermittent with vibration or temperature.

You can test for items 1 and 2. Since failures of transformers in general are unusual, the intermittent failures of item 3 are downright rare. Not impossible, but rare.

To test a transformer, you need

- an application schematic, showing how it's connected, particularly what transformer leads are connected to internal windings

- a multimeter that will measure AC volts and ohms

- a source of low voltage AC, like a filament transformer output

- a neon bulb, like an NE-2

- a battery; the 6V lantern/flashlight battery is ideal.

Test 1: Winding shorts and opens

- Disconnect the transformer from the circuit so the circuit does not give you false readings.

- Set your multimeter to ohms and measure the resistance of each winding. You're looking not for a specific value of ohms, but for the difference between a possibly long length of copper wire and an open circuit. Windings may be a fraction of an ohm, or may be a few hundred ohms. But they are NOT 1M or over. So it's easy to tell.

Each lead shown on the schematic as being connected to a continuous winding must show *not* open circuit to all other leads on that winding. If one or more leads on a winding are open to the others, the transformer has failed. Then measure resistance between windings; it doesn't matter which of the leads on the windings you pick, as the resistance between any two leads on different windings *MUST* be an open circuit.

If there is a resistance, or worse yet a very low ohms value, and the schematic does not show that they are connected, there is an internal short. Notice that you MUST open up any external connections that may cause an external connection of the two. Two unused leads accidentally touching each other or the chassis can cause a false positive.

- Make sure *all* windings are open. Connect the neon bulb across any winding. Doesn't matter which one. Pick a winding, doesn't matter which one, and temporarily connect it across the lantern battery. If the neon bulb flashes when you remove the connection to the battery, there is no internal short inside a winding. Notice that any external loading or connections can show a false failure on this one.

- If it passes all that, it's almost certainly good. To be extra sure, again make sure that all leads are open, and then connect the low voltage AC source to one winding. Low voltage windings are preferable but not critical. Measure the AC voltage on each winding section. There should be an AC voltage proportional to the winding's ratio to the winding being driven.

That's it. If it passes all of those, the only possible flaws left inside are latent ones, things that only short or open under high voltage stress or high temperatures. As noted, these do occur, but are quite rare.

Questions?

) and don't do this to transfomers that are too small.

) and don't do this to transfomers that are too small.  I'll try again.

I'll try again.

Comment